Passengers are the very raison d’être for airlines, and as the world aviation industry heads for Le Bourget and the Paris Air Show, we’re doing a deep dive into how both of the primary airliner manufacturers are entering the show, at the intersection of the airframer reality and the passenger experience perspective.

We’ll start with Airbus, not least because the European multinational is entering the starting grid for the 2025 Paris Air Show in pole position ahead of its US rival, both in industry terms and in recent passenger experience innovation.

Airbus ended up ahead of Boeing in deliveries in 2024 and remains ahead in 2025 plans, even as Boeing hits 38 aircraft per month on the 737 MAX line, resolved the 777-9 engine thrust link problem that grounded the test fleet, and in February closed the “shadow factory” in Everett for 787 programme rework.

With ongoing questions about global political economics, Boeing’s own capabilities, the further delays to the 777X, and the certification of the 737 MAX 7 and 10, Airbus certainly has advantages. But not all is plain sailing in Toulouse, especially with ongoing supply chain problems — including a return to interiors production issues on the A350, particularly lavatories — A320neo family engine issues, and competitiveness questions between the A350 and the much-delayed, yet larger, 777X.

How the Le Bourget home turf, geopolitics and airplane diplomacy affect the show, and the airframers

Airbus has historically used its European — indeed, French — home ground advantage at the Paris Air Show for big announcements. Both the Le Bourget announcement lever and the being-in-Paris lever are useful for Airbus to be able to pull in negotiations, especially the last minute airshow type that make the week so exciting, but at the same time savvy airline and lessor customers know that Airbus is keen to make deals, at least where it has capacity to deliver those deals.

In terms of those deals, it’s a notable sign that Airbus registered a big zero for new orders in May 2025, the month before Le Bourget. There weren’t even any “chalk them up now, announce them later” orders for that old airshow chestnut, Undisclosed Customer Airlines. That suggests a certain amount of saving up of orders to announce at Paris.

Airplane diplomacy is another crucial lever for the show, but it’s a lever that swings in multiple directions, bringing both advantages and disadvantages in Le Bourget announcement terms. On the one hand, Airbus can lean on the pomp and circumstance of Paris, plus the proximity of French and other European leaders, to entice foreign governments and their associated airlines.

On the other, major customers — most notably Chinese airlines but increasingly those in the Gulf — love in their turn to entice European leaders to visit, especially during key anniversaries, and have successfully dangled large orders from Airbus (and other aviation manufacturers like Dassault) to do so.

That’s airplane diplomacy for you, and at a time of exceedingly fraught geopolitics for Boeing in particular, Airbus has a clear diplomatic advantage with the US-China trade conflict. Ahead of the planned July visit of European leaders to mark 50 years of diplomatic relations between China and the predecessors of the EU, Bloomberg’s Siddharth Philip and Danny Lee report an order of somewhere between 200 and 600 Airbuses for Chinese carriers that might come about during the visit.

The Paris Air Show implications, of course, would be that if this airplane diplomacy order happens in China, it won’t happen at Le Bourget.

Early movement around the prospective China order includes the announcement on 10 June of 19 ATR 72-600 aircraft, plus 3 purchase rights, by UNI Air, the regional arm of EVA Air based at Taipei’s (smaller, city-centre) Songshan Airport.

This is the largest order for ATR — a European airframer owned by Airbus and Italy’s Leonardo — in eight years, so all other things equal one might have expected it to take place on the home turf at Le Bourget. Bringing it before the show suggests that Airbus might not want its order to be caught up in China-Taiwan politics, suggesting that there is indeed a deal around which such sensitivity is prudent.

Before leaving airplane diplomacy, a quick detour via public diplomacy, a topic which your author has been following for nearly a quarter of a century since it was the focus of his MA International Relations dissertation. Public diplomacy airlines — in the aviation context, investing in national airlines to improve the image of a country, especially overseas — has long been a part of aviation’s history, from the gleaming national carriers of the jet age to the EDB/Temasek ownership of Singapore Airlines, to the Gulf Three, and most recently with Saudi Arabia’s revitalised Saudia and startup Riyadh Air.

From an airline perspective, public diplomacy airlines essentially get to play the airline management game with an unlimited money cheat code. It’s been informative to observe a regular stream of aviation industry (and in particular passenger experience) professionals being headhunted for Riyadh Air and Saudia over the last couple of years. Indeed, the large airplane orders, glossily designed futuristic cabins, and swanky luxury amenity kits that have resulted are a useful yardstick for what it is possible to design in the world of commercial aviation if money is not a factor.

In advance of the Paris Air Show, Airbus repainted one of its A321XLR test aircraft — F-WWBZ, the previous Miami-London, Kuala Lumpur-Sydney livery one — in Riyadh Air’s mostly white colours. The aircraft flew from Hamburg to Le Bourget on Thursday 12 June and will presumably be displayed on the stand. There are also rumours of an A350 order, but timing questions for these aircraft remain.

The airplanes question remains: what exactly does Airbus have available to sell?

Moving on to the “airplane” part of “airplane diplomacy”, in this context Airbus has a strong order book, which is definitely a business class problem to have — but to fulfil them it relies on a still-creaking supply chain that has airlines and lessors less than delighted. To a certain extent some of this supply chain trouble is out of Airbus’ control, especially around engine suppliers, but it’s nonetheless a problem.

Slowing A320neo family production and Pratt & Whitney geared turbofan reliability has been a major issue this year — Wizz Air’s need to ground some 20 percent of its fleet for engine availability, with more than a sixty percent drop in its operating profit, is an example of the problems Airbus faces with customers. The interiors supply chain is improving, but is still not where it needs to be.

In terms of its airplanes, Airbus currently offers nine commercial passenger aircraft across four aircraft families:

- A350

- A350-900

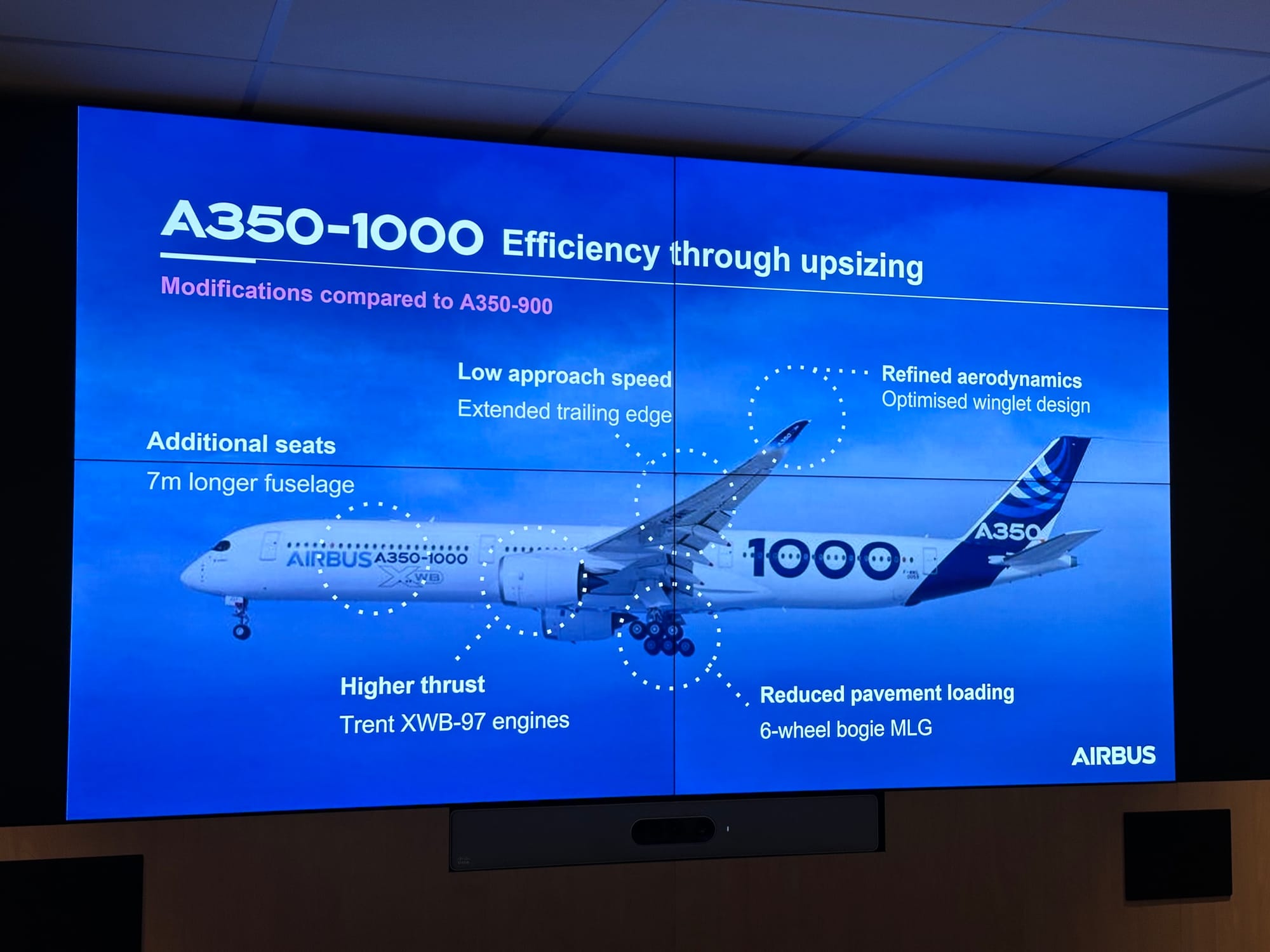

- A350-1000

- A330neo

- A330-800

- A330-900

- A320neo

- A319neo

- A320neo

- A321neo

- A220

- A220-100

- A220-300

In the short term — to 2030, a nice round five year number — Airbus only really has substantial delivery space for sizeable orders in the A220 and A330neo categories. The A320neo is booked through to the early 2030s, a little further than the A350. With production capabilities, supply chains, and rate increase prospects the way they are, it’s hard to see an A320 rate hitting (let alone exceeding) 75 per month, or much scope to raise the A350 above the long-term plans of 12 per month.

Some of this order book constriction could be massaged slightly with negotiations, or rather with renegotiations, including around when and how purchase options firm up.

Airlines with a sizeable A321XLR order, for example, might consider converting some of those orders to A330neos, where Airbus’ longstanding policy of flight deck commonality now means that carriers can used single and mixed fleet flying to combine pilot pools between its Airbus aircraft with the exception of the Bombardier flight deck designed for the A220.

In terms of new versions of these aircraft to potentially add to the mix, the options include stretches to:

- the A350-1000, a notional A350-2000

- the A321neo, a notional A322neo, including LR and/or XLR versions

- the A220-300, a notional A220-500

Of these, Airbus has most recently been talking up the notional A350-2000. With the end of the A380 programme, it’s clear that Boeing has won business on its 777-9 stretch of its largest production twinjet over the A350-1000, and that this has not gone unnoticed by Airbus. (Keep reading for more of the nuance around this new flagship A350 aircraft.)

With the performance and order dominance of the A321neo over the competition (especially the LR and XLR variants), the as-yet-uncertified 737 MAX 10 (an aircraft with much less range and mission capability) and with some seven years of orders in the family backlog, the pressure for the A322neo is substantially less.

That pressure is, however, not absent. A larger A320neo family member is, pure and simple, more profit for Airbus than a smaller one, and an A322neo takes up the same notional production slot as an A320neo. Indeed, airframers have long been content for airlines to order (and pay the deposit for) a smaller family member and then later upgrade to a larger one closer to delivery. This approach also inherently has inflation adjustment benefits to pricing. Offering the A322neo also enables some renegotiations that might free up slots.

The A330neo might well end up being the story of the show: there’s a sizeable replacement market at the smaller end of the widebody scale, business class and premium economy are profitable and new products are stretching further backwards than in previous cabin configurations, the airframe is relatively inexpensive in terms of capital outlay, and a Rolls-Royce Trent 7000 engine that has — with fingers firmly crossed — achieved a reasonable reliability level.

Airbus’ key focuses include the A320neo successor, a return to the MOM, and the flagship question

The A320neo successor aircraft is a key question for Airbus, which has been mooting a launch of the new airframe in 2030 and entry into service at the end of the 2030s, which a reasonable observer with an eye on the history of airplane development, and especially recently powerplant innovation, would suggest probably means “2040 if you’re lucky”.

There are murmurings from various current A320neo family customers that Airbus should be concentrating on delivering its current aircraft and keeping them in service rather than moving its attention elsewhere. These are understandable, but at the same time it makes sense to involve industry early and often with the successor airplane.

We will no doubt be returning regularly to the question of this airplane, because whatever happens Airbus will be creating an A320neo successor aircraft. But today, it certainly seems sensible to start publicly floating the concept of what the next Airbus narrowbody — likely to fly to the 2080s and beyond if the A320neo’s 40-year-plus history since 1986 is replicated — might represent in terms of airline and lessor customer needs.

Key questions for dicussion that are already known include:

- basic design shape: an updated winged tube versus a new configuration like a blended wing body

- wing: single wing, transonic X-66 style, or something else

- fuel: aviation fuel, sustainable or not, or (much less likely at this stage) alternate power sources like electric

- powerplant: turbofan or open rotor, and whether single or multiple powerplant options

- size: similar to the A320neo family or sized for sweetspots of 150, 200 and 250 passengers at key densities?

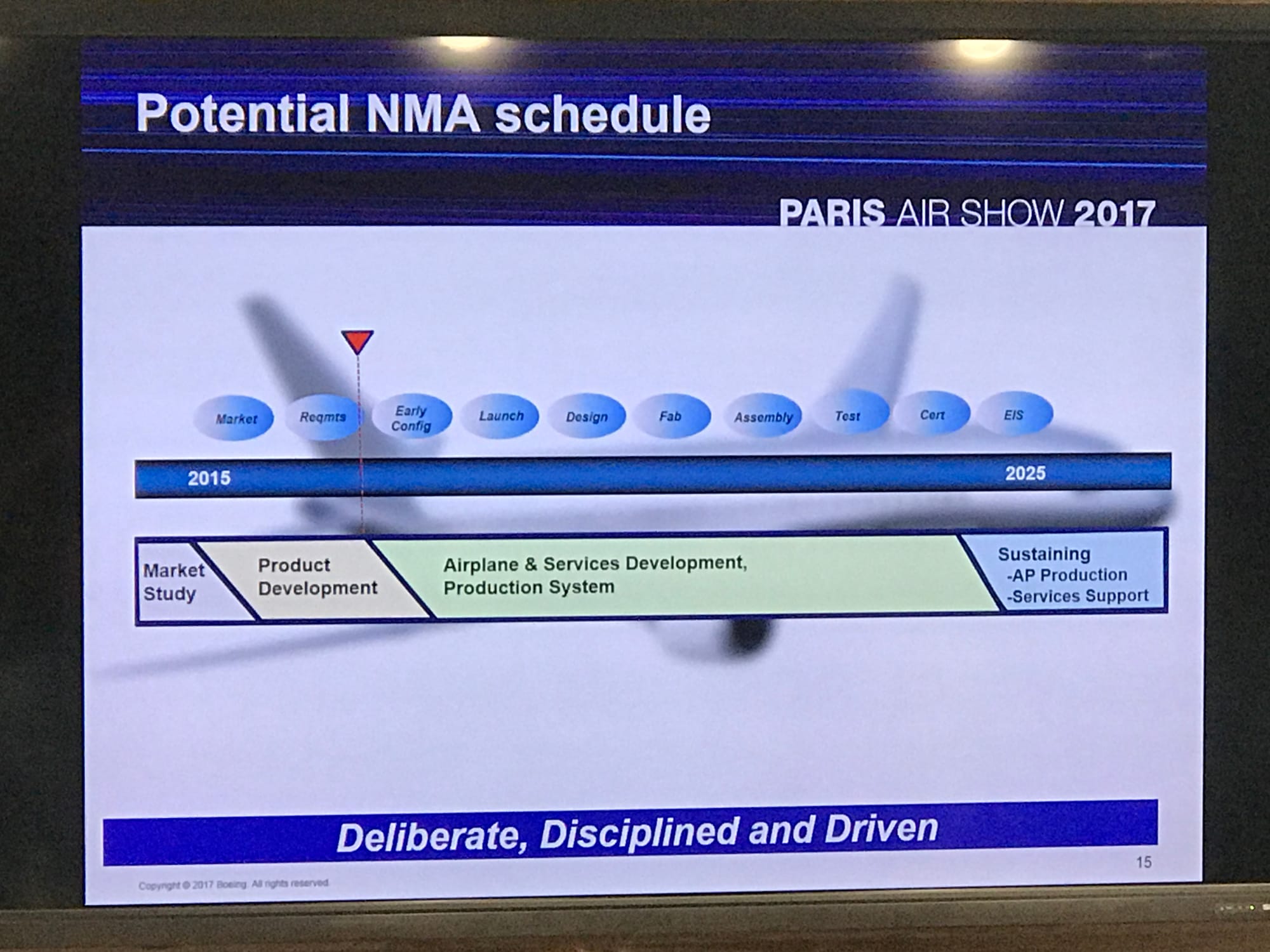

If you’re thinking this all sounds a little like a return to the middle of the market discussion that has been quiet since Boeing last spoke about its options in this segment, you’re not alone.

This is an important, high-demand, lucrative — and at its upper end underserved — segment, and developments here will have major impacts across aviation from the passenger experience to airport infrastructure and beyond.

Moving upwards in terms of capacity and prestige, though, is the notional A350-2000 stretch. The A350 was always intended to be a three-aircraft family, with the -800, -900 and -1000 models sitting below the capacity of the A380. With the -800 never launched, and indeed with the A380 now out of production — what is it about Airbus models with an 8 in them, from the A318 to the A380, the A330-800 and the A350-800? — the natural question as whether a further stretch of the A350 makes sense.

For many airlines, it might. As much as successive Airbus sales chiefs might coin monikers like “the long range leader”, and despite genuine improvements — like the 2019 larger A+ door (enabling the new 480 maximum passenger count on the A350-1000 as used by French Bee), the 2022 New Cabin Standard/New Production Standard upgrades, plus other performance revisions — the size and capacity of the forthcoming 777X are simply greater. For airlines, it’s telling that, with the sole exception of ANA, all commercial airline customers for the 777X are already A350 customers as well.

These 777X aircraft will likely, for many airlines, become their flagship product. The extra width of the 777X cabin compared with the A350 brings benefits at the front of the airplane in particular, with first and business class suite seats and doors already creating space squeezes.

Airbus seeks to improve A350 first class offering with a new forward cabin configuration

First class has been declared dead even more times than I have written that its death has been greatly exaggerated. Today, it’s clear that there remains a steady core of airlines for which a product above business class makes sense.

Modern first class means suites: big ones, especially as business class mini-suites have grown in size, space, features, and privacy.

In the 20 years since the introduction of first class doored suites by Singapore Airlines, and as airlines transitioned from their flagship halo products existing on the A380 to the 777 and A350, we can divide them into six key categories:

- first-generation suites, as on numerous airlines’ A380s at launch in the mid-2000s: Singapore, Emirates, Asiana, plus Korean Air’s 747-8

- one-aisle perpendicular suites upstairs on second-generation A380 cabins: Etihad, Singapore’s current A380 design

- second-generation suites: ANA’s The Suite, Swiss 777

- floor-to-ceiling suites, like Emirates’ 777 Gamechanger suite

- 2020s suites, including double-suites: JAL A350, Lufthansa FICE/Allegris/Swiss Senses, Qantas A350 Project Sunrise, British Airways’ new A380/777X suites, and Airbus’ new A350-1000 concept

- front-row business-plus suites: Starlux

This breakdown excludes non-suite products, like Lufthansa prior to Allegris and Korean Air’s A380 cabin, as well as front-row business-plus suites not sold as first class: jetBlue Mint Studio, Condor, Lufthansa FICE/Allegris Business Suite, and so on.

Today, the top of the range here are the airlines reinvesting in new full first class products, which are being retained by most European, Middle Eastern, and Asia-Pacific carriers that already offer them, including most notably Air France, British Airways, Lufthansa & Swiss, Cathay Pacific, Emirates, Etihad, Singapore Airlines, Japan Airlines, All Nippon Airways and Qantas.

Meanwhile, United and American barely gave me enough time to remove United Polaris First and American Flagship First from my giant spreadsheet of onboard product types before introducing United Polaris Studio and American Flagship Preferred Suite front-row business products.

In contradiction to much received wisdom on the topic, first class isn’t just becoming the province of airlines that operate as extensions of their foreign ministries as public diplomacy or national image improvement efforts rather than (or rather than primarily) as profit-making companies.

At the same time, the delays to the 777X have meant several airlines have launched their latest products on the A350 instead — or, indeed, on last-generation 777-300ERs.

To meet a demand for new first class products, it was fascinating to see Airbus’ biggest message to the industry at this year’s Aircraft Interiors Expo — just over a month before Le Bourget — was an improved first class on the A350.

Airbus is implementing a major reorganisation of the front end of the A350 between the flight deck and doors 2, specifically for the A350-1000, which it calls “our flagship aircraft”. Airbus tells me that they’re aiming for new linefit aircraft from 2029 with this plan, which has four specific elements.

First as passengers board the aircraft is a new welcome area, with a sculptured ceiling and a customisable welcome light panel that airlines can customise.

Second is a new ceiling structure where the cabin intersects with the overhead crew rest at the very front of the cabin’s centre section, pushing the roof upwards and adding a new lighting panel to create a sense of more height in this area.

Third is a new arrangement for the area of the forward lavatories, which at present are arranged with one behind the flight deck and one behind doors 1 if the airline wants two first class lavs. Here, the entrance to the pilot overhead rest area is moved out of the first class passenger area, while a larger space for the lavatory ahead of doors 1 enables either one bigger lavatory, a lavatory with changing space inside, a storage zone closet, or a dedicated changing space outside the lavatory, as airlines like. Here, Airbus is going out to airlines to see what they want, without passing out much in the way of renderings or suggestions.

Fourth, Airbus is creating a double bed option in the centre that has its own lavatory attached internally, a little reminiscent of the Etihad A380 Residence product, though with a sofa bed rather than separate bedroom. This double bed space concept is wrapped by a curved screen and offers a two-person loveseat that also has a two-person partner dining area, although the table is only about 5/8ths the width of the double bed in Airbus’ renderings here.

There’s also a space that could either be a private lavatory or, as Airbus is rather inexplicably showing it, a sort of changing area with something that looks like a vertically oriented LP record player, which passengers will use for, what, five minutes of their longhaul flight, in a suite that already has fully closing doors so they can change to and from their airline PJs in privacy?

I’m all for thinking outside the box, especially when creating suites that are, well, an actual box, but this is once again from Airbus an odd decision to create renderings that pass by wild and wacky to feeling like they lack a grasp on the reality in which airlines and designers are optimising for space in constrained cabins.

Fundamentally, the A350 lacks the A380’s “forehead” space outside the cabin footprint that meant Etihad’s Residence didn’t pull space from elsewhere in the first class cabin, and even that didn’t have a changing room (or an LP player).

Here, some reasonably prime real estate is being taken up: it’s not full centre section width because this is ahead of the taper point where the aisle needs to bend towards the galley, but it’s still wide enough to accommodate the ottoman and partner dining seat space if needed.

It’s sort of the reverse side of the coin of the Airbus Airspace cabin renders that seemed to live in a universe where lavatories and galleys didn’t exist, and nor did bulkhead partitions, with swish business class pods opening straight onto door 1 galleys, or cabin transitions with zero dividing walls between economy and business class, just open air.

At a time in the industry where these transitions — and, genuinely, I’ll include the transition in this new first class module from the double-centre suite to the lavatory and crew rest unit in front of it as a transition — are some of the most complicated parts of the puzzle for cabin designers, it would be really helpful for airframers to anchor their thinking in the real world.

Airbus’ evolution of these ideas will be instructive to observe, at Le Bourget and beyond.

Make sure you’re subscribed to The Up Front for all our on-the-ground news and critical industry intelligence from the Paris Air Show — including our daily live feed, flash audio updates, nightly readouts, and much more.