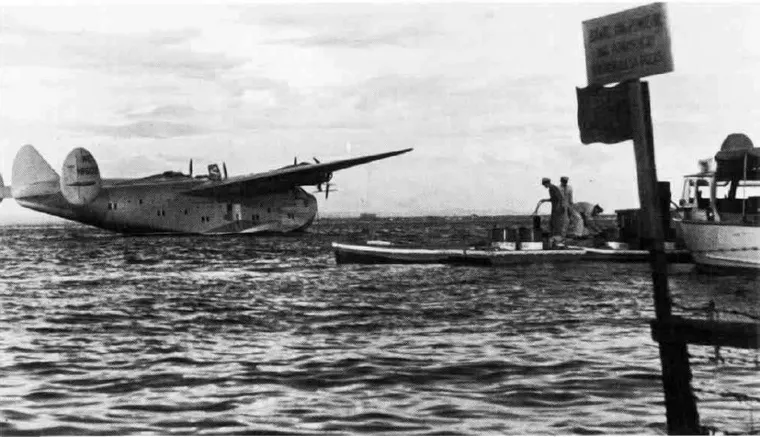

We continue our series looking at one of the most stunning, yet near-forgotten, acts of skill in civilian aviation history: the round-the-world flight of the California Clipper in December 1941. You can find the first part of this series here.

“Swede,” Ford later remembered telling his flight engineer with concern, as the patrol boat carried the men ashore for breakfast, “they can only give us regular gas.”

The Dutch air station at Surabaya (in modern Indonesia) was more than accommodating to the California and their crew. They provided radio frequencies for the British base at Trincomalee (in modern Sri Lanka), the crew’s next destination, and signaled ahead to warn the British that the California was coming.

The base doctor vaccinated the crew against a variety of diseases they were likely to encounter on the remainder of their attempt to fly round the world to New York. The quartermaster provided supplies and the Dutch maintenance crews were happy — and by some accounts excited at the opportunity — to work on a Boeing 314.

What the Dutch were not prepared to do was part with any of their limited supply of high-octane military-grade aviation fuel.

This was a problem. The Boeing 314 was the only commercial aircraft in the world that required military-grade aviation fuel to run. It wasn’t just that the California wasn’t designed to fly on regular gasoline, it was that no-one even knew if she could. It had never been attempted. There was simply no telling what would happen if they tried.

She might not be able to draw enough power to take off. Even if she managed to get airborne, the rate the engines would need to run at to generate sufficient power from the lesser fuel quality might cause them to overheat and blow up. All these things were possible and more.

The crew had been able to dodge this problem so far on the trip. The California’s fuel capacity was vast. It needed to be so that she could fly the lengthy hops required for her to island hop across the Pacific. As a result, when they’d been unable to find military-grade fuel at Gladstone they had simply opted to push on to Darwin.

The Dutch were adamant, however. They did not have enough military-grade fuel to spare for the California’s desperate attempt to get home the long way round. They needed every drop for air defence.

The fuel gamble

While ashore at Surabaya, Swede Rothe and the Pan Am flight mechanics that had been with the California since New Caledonia tried to work out the least-risky way to transition their aircraft to using regular fuel. Something that played into their favour was that the California’s fuel tanks were fully compartmentalised. She had fuel tanks spread throughout her wings (her “outboard” tanks), and more in the main fuselage (her “inboard”). They could also pump, and switch, between them at-will.

In the end, they decided to concentrate what little military-grade fuel they had left into the inboard tanks. They would use this for take-off and landing. The outboard tanks were filled with regular gasoline, which the Dutch were happy to supply in unlimited quantities. They would attempt to switch to this during flight at cruising altitude.

This plan limited the risks created by running on a never-tried fuel blend. While cruising, the engines were under less pressure to perform. They could be run at lower speeds. The lower air temperature would also help keep them cooler.

It was a good plan, but as Ford would later recall he did point out one key assumption within it: it presumed the California could run on regular fuel at all. They would now only find out if this was true when they were high above the ocean. If she couldn’t, then they may not have enough military-grade fuel onboard to safely turn back to Surabaya. The results might be fatal.

In the end, it was agreed that they had to try. The next day, loaded with fuel on which no Boeing 314 had flown run before, the California departed on the longest leg of her journey so far: The 2,500 mile flight over the ocean to Trincomalee.

Backfires

Ford later claimed that the flight between Surabaya and Trincomalee felt like one of the longest in his life.

Shortly after take-off, the crew switched the California’s four high-powered engines to draw fuel from her outboard tanks. Almost instantly, the consequences became clear.

Bang.

The California shook, as if in a violent storm. And Swede, sat at the engineer’s station, flinched.

Bang.

“Backfiring on number three!” Johnny Mack shouted.

Bang

Internal combustion engines rely on being able to combust. They use a series of small, controlled explosions in a regular pattern to drive pistons. The movement of these pistons translates into power. The better the fuel, the less of it you need in the combustion chambers at any given time to create the explosion. The better the explosion the less frequently you need your pistons to be moving to generate the level of power you need. This stops your engine overheating.

Bang.

For a high-performance engine, like the four super-charged Wright Aeronautical Cyclones on the Boeing 314, knowing the performance curve between fuel, power, and engine heat is vital. Push one of those variables too far out of balance and bad things happen.

Bang.

Those bad things were now happening to the California, and they were happening high above the Indian Ocean. Her pilots and engineers tried desperately to work out the performance curve for running a Boeing 314 on regular gasoline, rather than the military-grade fuel she was designed to run on.

Bang.

They needed to find out how ‘lean’ they could run the fuel to keep the California’s engines from stuttering to a stop. They couldn't keep running the engines at maximum power to compensate for the lesser fuel quality. It left the engines too hot, drastically increasing their chance of failing mid-air. It also consumed too much fuel, given the distance they needed to cover.

Bang.

They had to find a way to run her lean, but the bangs now shaking the aircraft violently were her engines starting to backfire. A sign the fuel was too lean for them to function on. The more frequent the bangs, the closer they got to an engine shutting down or worse: simply tearing itself apart under the repeated, juddering assault.

It took many long and nervous hours before the crew found a lean mix of regular fuel on which the California would just about agree to fly. It left her engines just above the level where the backfiring would start, but it came with two huge compromises.

The first was that her engines were now running close to their red line in heat management. They were asking the California to run near the upper limit of her safe-performance range for the entire journey, without rest.

The second was that it meant they had to fly far lower than their regular altitude. They couldn’t afford to be at altitudes where the air got thinner. The engines needed all the help with combustion that they could get.

The approach to Trincomalee

Fuel wasn’t the only issue for the California. Sat back from the cockpit, her navigator Rod Brown had his own problems. Using only the atlases and charts they had found in New Zealand, he had been trying to plot their course from Surabaya to Trincomalee. This would have been hard enough with detailed route information. It was even harder when the last positive land sighting he had to work with was the northwestern end of Sumatra, passed early in their long flight.

Navigating vast distances over oceans was an art form that Pan Am had been forced to perfect. They were pioneers in radio direction-finding as a result, equipping their planes and bases with near-military grade, cutting edge direction-finding equipment. Brown had none of that to rely on here. He was forced to return to the kind of navigation instantly recognisable to a 19th-century sailor. Maths, magnetism, stars and dead-reckoning. There was no other option. Luckily, Pan Am trained their navigators well.

By morning of the 21st December 1941, the California had been airborne over the featureless ocean for almost 19 hours, flying on Swede’s careful fuel balance and Brown’s best-guess route. They knew they should be nearing their destination, but the layer of low-lying cloud beneath them was a problem. Brown asked if Ford could drop beneath that layer in the hope that land would be visible.

Ford agreed to the request. Soon, the California was flying a mere 300 feet above the waves. Like medieval sailors, her crew began scanning the horizon from her windows, hoping for a sight of land.

For some time, they saw nothing. Ahead, out of the cockpit, the sea was calm and unbroken. Well. Not quite unbroken. They were closing on a narrow dark shape motionless in the water ahead. It was Johnny Mack, sat in the co-pilot’s seat, who spotted it first. He pointed it out to Ford, suggesting it might be a whale.

Ford later recalled following his first officer’s gaze to the object. His eyes flew wide.

“Submarine!” He shouted.

The speed of their approach meant the conning tower was now already visible, a Rising Sun painted on its side. It was Japanese. Men were already running towards the large gun on its deck.

Ford bellowed at Swede Rothe to switch the engines to the better fuel and push the California to full power. This low and slow they were a sitting target for the submarine’s anti-aircraft fire. They needed speed and height, fast.

“They’re aiming that thing at us!” Mack warned.

“Max climb! Let’s get the hell out of here!” Ford remembered shouting.

Ford and Mack hauled back on the yoke desperately, fighting the sluggish controls as they sought safety in the cloud cover above. The California blazed directly over the submarine mid-climb, the deck gun swinging round as it started to track them through the sky. It was now a straight race between the speed of the submarine’s gun crew and the plane’s climb rate.

Finally, after what felt like an eternity, the California reached the clouds. As they burst through into the blue sky above, a bright flash from below illuminated the cloud layer below them as the submarine fired. The men on board the California braced for impact. Luckily, it never came.

Ford left it as long as they dared before dipping the California beneath the clouds again. This time, to the crew’s relief, they sighted land. In a supreme act of aerial navigation, Brown had put them almost exactly where they needed to be. No one was likely more relieved about this than Brown himself. An hour later, the California Clipper was down and secure at the British air and naval facility at Trincomalee, to the relief of everyone on board.

None of her crew now carried any illusions about the challenge ahead, both for themselves and the California. From here on, they would be asking for more performance from her than had been asked of any aircraft in that class before.

And they were still almost 14,000 miles from home.