In the early 1990s, British Airways began designing a new type of first class seat. Eclipsing the sleeper seats of the time, it converted to a bed and arranged in a tessellating herringbone pattern within the nose of the carrier’s dozens of Boeing 747 aircraft, it changed the game in premium travel, accelerating developments up front including the first fully flat business class seat (the original “Mohawk” Club World flatbed, 1999) and the first fully flat business class seat with direct aisle access for every passenger (Virgin Atlantic’s Upper Class, 2003).

Some thirty years later, tangerine is squeezing its creative juices for BA with a next-generation first class suite, and The Up Front sat down for an in-depth discussion with the design agency’s creative director Dan Flashman about the product — and the project.

British Airways, Flashman tells us, “ran a competitive pitch, with pretty much every agency in London in the industry, I think, whittled it down to three and took those a step further. From that, they selected our first class concept to go forwards. What I think is quite good is that our concept at that stage actually quite closely resembles the final product right now. There was another sort of dimension to the concept at that stage, which didn't make it through, but apart from that, it looks pretty similar.”

The new suite is the the biggest change in BA first class since that mid-1990s product: the intervening years’ “Prime” generation of seats started rolling out largely as a look-and-feel upgrade on the same herringbone tessellation pattern in 2010, later evolving to a doored product on some aircraft from 2020, but this is the generation that earned British Airways’ First the frankly deserved nickname as the world’s best business class, especially after the Cathay Pacific/JPA Design 2010 improvement of the Safran (previously Zodiac/Sicma) Cirrus herringbone seat in business class.

Prime was in many ways the zenith of the automotive-influenced aesthetic in first class that now feels dated: the twisting dial for the seat controls, the seat stitching, the glossy surfaces, the early LED lighting, the cold blue-white starkness of the accent colours.

For the new suite, Flashman says, “we wanted to go a lot more residential, a lot more hotel room, a bit less automotive, because this one particularly is more of a room than a seat than previous versions: walls are higher, you're sat back further, it feels more like an environment, rather than being in a seat with some small partitions. The seat fabric has a much more busy weave. We've much more texture going on in there, which gives it a much more residential vibe. It's much more sofa-like than car seat-like. There's not those lines around the back support that you often get — no go faster stripes at all.”

There’s an intriguing mix of these soft residential elements with other more structural design points too, such as the Concorde-inspired lamp that curves in a satisfying, almost organic way.

“For BA in terms of being luxury, it's not an overpowering bling, it's quite understated — there’s a lot of brushed nickel, which is an expensive finish, but it's brushed and it's slightly satin so it it's not screaming at you, but when you look closely at it, it’s very beautiful,” Flashman explains. “I think that feels very British Airways: it’s kind of effortlessly there.”

The blues, neutrals and silvery nickel metals are the majority of the colourways in the seat, but “when we do sort of shout in terms of the palette, it's when you open a cupboard or something like that: there's this bright red leather, which is obviously very BA, but it's, only when you open a compartment, but you that you see that big flash of colour,” Flashman says. For example, inside the compartments, “we went to quite high length to get some quite good stitching and upholstery detailing in there, to get across the quality, pushing our suppliers as far as we possibly could, and then a little bit further.”

This isn’t just helpful in that a dropped wallet, passport or other personal item will stand out against the bright red of the compartments: it lends a pleasing sense of whimsy in the aesthetic, and harkens back to British Airways’ extensive heritage.

Your author couldn’t help but liken the red shape created by the lower pull-out storage compartment to the thin red line that opened up at a strong angle into the wider stripe of the speedwing motif of BA’s 1980s Landor livery — but, it seems, this was quite the accidental reference rather an intentional easter egg.

“I'd love to say it was, because it's my favourite livery — the Landor livery just says class to me — but that is just a happy accident,” Flashman admits. “But I love that it looks like that.”

Pushing the boundaries between aesthetics, materials, and certification is crucial, yet complicated

Colour, materials and finish — CMF, in industry acronym lingo — make any product sing. Examples abound of airlines operating the same seat, but with wildly different investments in the aesthetics. In BA’s new suite, the warmer wood, quilted headboard effect rear wall, and the texture of the seat fabric are coherent and generous — but are also highly engineered.

“We wanted the dress cover to look as sofa-like as possible,” Flashman says. “I want it to look comfortable and fluffed up, but it's got to look like that every time. These are sofas that are really, really heavily used. There are some really tough requirements: the fabric has to have some wadding in the dress cover, but also be laminated, so that it looks soft, but it's also not going to be wrinkly and awful after 20 flights. It’s quite soft at the surface, and then there are some foams of different density to make it as soft as we possibly can, while also passing the 14g downward test.”

That downward dynamic testing is just one of the certification requirements needed to show compliance with increasingly strict regulations around structural integrity, impact resistance, flammability, heat release, smoke toxicity and other elements — even before the recent complications around egress and depressurisation are considered.

“Obviously, there are lots of sort of hurdles to jump through, requirements that you learn more about as you go through the process. We've done a lot of these programs, so we have a pretty good guess of how things are going to turn out in the wash, as it were,” Flashman says. “It’s complicated. I do feel sorry for the people that are making sure that what we're putting on is safe, from Boeing and from Collins, who have to make sure that everything's safe, because we're always trying to push things further and further along. It’s no longer just a seat, which the [certification] requirements started out allowing for, it's a whole room, really. We're trying to create hotel rooms in the sky, which is quite a long way from a regular seat that just reclines. The requirements get more and more complicated as what we're trying to do to get some more and more complex, but it's still got to be absolutely safe, so you've got to take that stuff really seriously.”

With more and more of the seat covering the sidewall and floor of the cabin, decompression is an increasing challenge for certification of premium seats, with the requirements to allow air movement at substantial velocity during a decompression incident while also retaining structural integrity.

“Visibility from the aisle is still a challenge,” Flashman also notes. “It's easy to create visibility, but it's difficult to create visibility while still making a passenger feel like they've got privacy. Flam [flammability testing] is relatively straightforward, because you're familiar with the manufacturers. and they know the requirements. Usually things go right: we know what's going to pass and what's not going to pass.”

That said, the stack-up problem — where materials that independently would pass flam testing, but do not as a whole combined element when combined together, often via glues or other adhesives — has tripped up a number of programmes.

Other challenges include emergency egress requirements for increasingly private products with higher doors and walls than expected when the regulations were written.

“Having three escape paths adds challenges, especially for suites with doors. We did some quite fun tests with seeing if people could climb over the wall in the required time, getting some naive subjects to try and escape from an MDF [medium density fibre-board] mock up,” Flashman says, noting that “there’s the double suite aspect of this particular design, and whether it can take off with that divider open or not, and whether it's safer for it to be closed or safer for it to be open. Are two passengers going to try and go out through the same door? That’s quite a big topic: where do Boeing and Airbus sit on dual occupancy?”

Accessibility for disabled travellers, passengers with reduced mobility (PRM) and wheelchair users was also a key requirement, not least because regulators require at least 50 percent of seats to be accessible from an aisle chair.

“BA was certainly very keen to really optimise the accessibility, and had very ambitious targets: not just half the seats, but all the seats being fully accessible,” Flashman explains. “We did a lot of testing getting wheelchairs down the aisle and then into the suite. There's quite a sophisticated PRM [passengers with reduced mobility] part of this suite, which involves some challenges. You want it to look like it's not there, but then magically and quite easily for the crew to fold away part of the suite to get loads of access.”

Combining accessibility with functionality and aesthetics is one of the holiest of grails for airline design, when access for passengers who need it also means function for passengers who might only want or like it.

Think the lowering armrest in Collins Aerospace’s MiQ recliner seat, used in regional business class, international premium economy or US domestic first: this enables easy level transfer from an aisle chair, but also lets more ablebodied passengers in the aisle seat lower the armrest to slip out to the lavatory during a meal, or to swing their legs sideways to enable their window or middle seat neighbour to slip past.

In the BA suite example, Flashman says, “I really like that the door completely disappears, and the front of the door goes back all the way and is completely flush with quite a curved and sculpted surface. I wanted it to feel like, when you get into the suite, you don't even know that there's a door there. Then you can push a button in the suite, and a door sort of magically appears and comes from nowhere. It was quite a lot of challenges in terms of getting a door to do that, and I'm very grateful that the team at Collins rose to the challenge.”

The hospitality concept has to move beyond separate seats and service, combining hard and soft product

As various airlines have found to their detriment over the years, a top-notch seat can only be a building block of the first class experience. It’s what the crew delivers, and how they deliver it, that really matters: an older seat can be eclipsed by superlative service, while the newest bells and whistles don’t matter if the food is bad and the service disjointed.

British Airways’ soft product — like service, catering, flatware, and bedding — is famously inconsistent. Good BA crews are great, bad BA crews are terrible, and in many ways there are fundamental disconnects between various core elements of the service delivery during passengers’ experience.

These disconnects manifest in several ways. The airline chooses industry-leading suppliers for its linens and bedding, but there’s a disconnect in the service loop, meaning that worn-out, pilled first class blankets are washed and put back on the aircraft, contributing to a shabby appearance.

For one example based on your author’s personal experience, BA first offers a good standard of Champagne and wines, but the crew were confused by the brut and rosé Champagne being from the same winemaker, and the bubbly was served at room temperature in clunky stemware. Elegant, quality glasses from names like Riedel, Schott and Lalique abound in first class, and the UK does not lack in glassware manufacturers that British Airways could showcase.

As another example: BA’s first class tea on this flight was, shockingly, the bog-standard Twinings yellow label, one of the UK’s most basic (and lowest rated) teas that you can expect to find in a cheap hotel in a leisure park next to a motorway, not in the luxury hotels whose experiences should parallel first class.

On the same flight, this mediocre tea was served in a pleasingly capacious teapot, yet brewed using only one teabag, making an insipidly weak pot, and with the tiniest of milk mini-jugs holding perhaps three tablespoons: about enough for one cup, and certainly not for a full pot. There are so many luxury tea companies around that the selection of Twinings was an unforgivable omission, and providing enough milk for a pot of tea is such a basic requirement that failing to do so seems bafflingly incompetent.

BA has now moved to Birchall teas, with the teamaker’s Great Rift blend on board in first class — a slight upgrade — but even this is still an inexpensive supermarket brand that, at the time of writing, was only 50p more than Twinings for an 80-pack at UK online supermarket Ocado.

First class often magnifies this kind of hard and soft product disconnect in an airline’s customer experience design, making it a useful study: if they can’t get first class right, what hope for business, premium and economy?

“Often the soft product and the hard product are done by different teams, and I think now airlines are learning that that needs to be more coordinated. It's done better when it’s all flowing together, and is from the same brush,” Flashman says. “Particularly on on this product, we were very keen that things aren't just sort of stuffed in a cupboard, but they're presented so in those cupboards: you have not just one compartment for the amenities, but several, and it’s designed around amenities being laid out and presented, almost as if it's a nice boutique store where you're seeing some nice face creams, whatever it is.”

Not to belabour the point on a poor showing of a flight, but referring back to that same BA first class flight, the amenities provided were Elemis, a high-street brand BA has used in its business class for decades. Elemis’ market positioning is complicated, but if it were ever a first class brand it is no longer, and the pots and tubes of product were stuffed into a lumpen, suede-effect bag that fell far below other airlines’ business class standard.

Whatever’s presented in the cupboards, the smooth blue cabinetry could be in an upmarket kitchen showroom: it does feel slightly like a kitchenette area in an airline lounge or hotel breakfast bar area, if the wireless charging area replaced the spot for the coffee cup in the self-grinding coffee machine. It’s certainly residential, but is it too much like flying in a kitchen for first class?

Flashman’s showcase desires, in any case, “probably created some challenges for the soft product team. The dream is that you'll get into the suite, and you'll open a cupboard, and there'll be something there that makes you feel special. Ideally, that's based on knowing that you want a particular kind of brand of tea, or whatever it is — that'd be a very special moment.”

It remains to be seen whether BA can remedy the disconnect between hard and soft product by the time the new suites are planned to launch on the airline’s Airbus A380s “in mid-2026”. That timing is, of course, dependent on manufacturing, with Collins Aerospace not exactly having covered itself in glory in its first class production capabilities in recent years. Lufthansa having to launch its anxiously awaited Allegris generation of seats with a loading symbol in an empty cabin instead of the Collins first class suites it ordered was one of the most visible supply chain management failures of the last decade.

In this context, it’s notable that Collins will be manufacturing the new British Airways suite in Kilkeel, south of Belfast — a first, it seems. On the one hand, there’s a benefit to having a fresh viewpoint on production (and a potential benefit at a time of tariff uncertainty) but at the same time Collins’ existing first class production sites and workforce are where the expertise in the category lies.

Beyond Collins, the suite is a showcase of British materials and suppliers: while the supply chain is inherently global, some fabrics come from Replin by Hainsworth in West Yorkshire, leathers from Muirhead in Glasgow, stitching thread from Amann’s site in Ashton under Lyne near Manchester, and so on.

The wider implications of the new suite depend on how widely it’s installed across the BA fleet

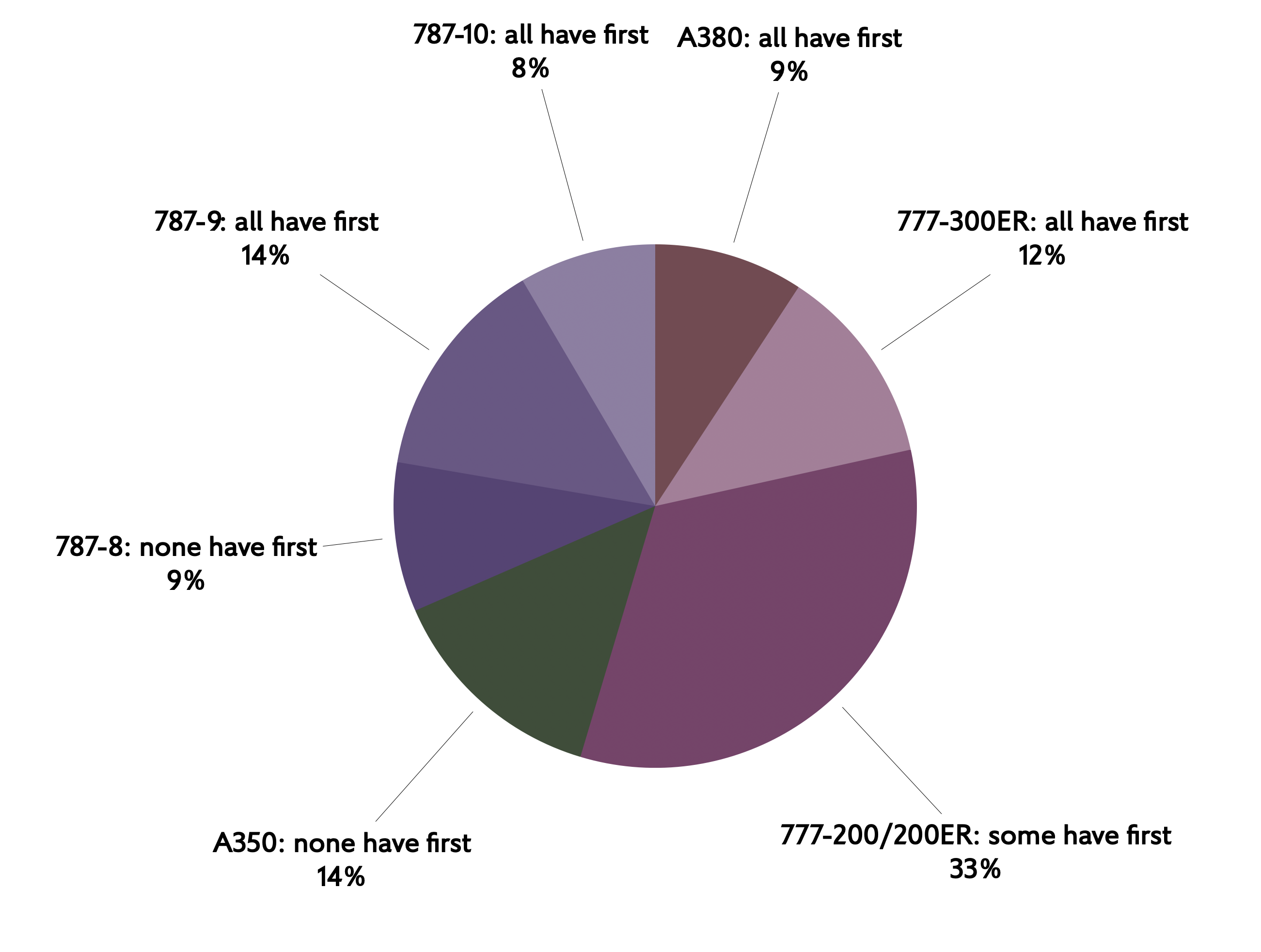

Much like inflight entertainment screens, rumours of the demise of first class have been greatly exaggerated. Airlines are investing huge sums of money to design and produce a proportionally tiny number of their seats, but with the halo effect alone the returns are clearly worth it.

Many tier 1 airlines (BA, Air France, Lufthansa, ANA, JAL, Cathay, Singapore, Emirates, Etihad) and a few tier 2 airlines (Swiss) are installing new studio-class business-plus products, while upstarts like Starlux are introducing studio class as a first class product, rather than as an ancillary upcharge to business class (like Virgin Atlantic with its A330neo Retreat Suite or Condor’s Prime Seat).

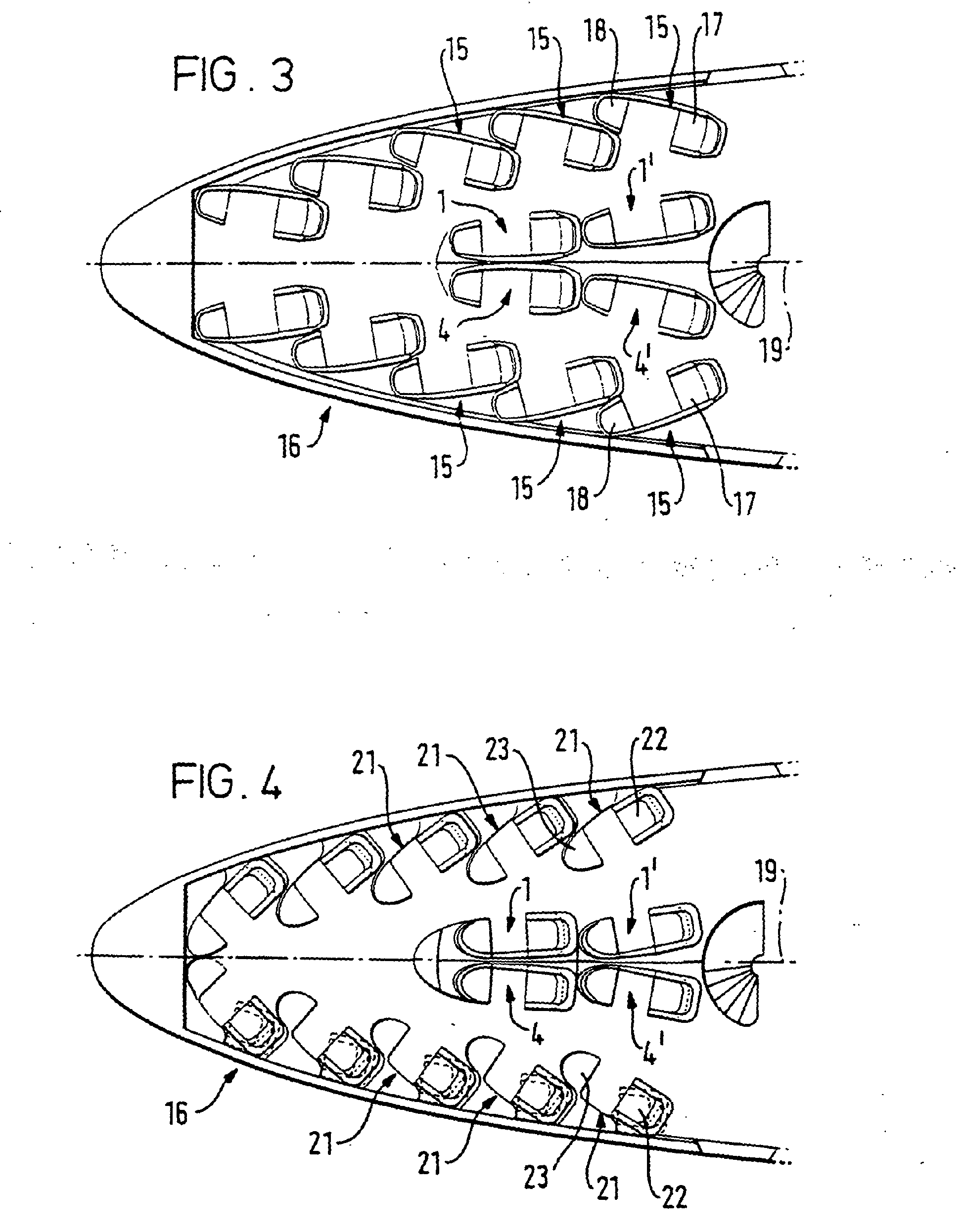

BA’s new suite should have good readacross to its other aircraft if the airline wants to bring them up to the new, post-Prime standard. A suite designed for the A380’s lower deck should work with a few adjustments on the smaller but still wide cabin of the Boeing 777X and probably on the second-generation Boeing 777s like BA’s 777-300ERs, although it seems unlikely older 777-200 and -200ERs will see it purely based on age.

A few more adjustments might work for the Airbus A350, although this might require some sort of double-suite option à la Lufthansa Allegris. A four-across doored suite in this generation on the Boeing 787 (let alone the Airbus A330neo) seems unlikely without some fairly major changes to the structure, in particular around removal or repositioning of lateral pieces like storage areas and wardrobes, but it’s not an impossible ask: Etihad and others have first class on the 787.

Pushing the boundaries of first class is always going to be at the very pinnacle of airline seating and cabin design, engineering, certification and manufacture. By definition, they are both pathfinder and halo product — even if Etihad’s The Residence never flew a single passenger, almost any mention of the airline included mention of it for years.

While the first class seats of 1995 have been eclipsed in space, privacy and luxury by business class seats for nearly a decade since the release of Qatar Airways’ Qsuite — in its first generation also manufactured by Collins — their influence continues to be felt. Will we feel the same way about 2025’s first class suites in 2055?

Continue reading at The Up Front with:

- our deep-dive analysis of the studio-class suite product generation that sits below these first class suites on many airlines

- United Airlines’ new Polaris and Polaris Studio suites, hard on the heels of this new BA product in aesthetics and raising the soft product bar

- more about us as we launch The Up Front — our people, principles and technology for bringing you a new type of independent aviation journalism

- why we created The Up Front, why we write, and how you can support our new model for aviation journalism

This article has been updated for clarity around the design houses involved with specific British Airways’ pre-2000 seats.