Whichever twenty-year passenger aviation market forecast you look at — and predictions from Boeing and Airbus are incredibly similar — there are clear expectations widebody production rates over the next two decades will be insufficient to meet fleet growth and replacement needs.

For airlines, this means that older aircraft will be required to fly for longer, and will likely mean demand for at least one more cabin retrofit cycle than today, perhaps even two.

This widebody retrofit market demand is beginning to be felt today, with airlines rolling out new seats that they had expected to first install on factory-fresh aircraft via retrofit programmes, as problems in certification, supply chains and production continue to bite in a strong demand context.

Indeed, consultancy IBA predicts post-Le Bourget that: “aircraft delivery lead times remain elevated due to supply chain disruptions and surging demand. Average lead times for near-term deliveries currently exceed seven years for A320neo, 737 MAX and 787 family aircraft, whilst the A220 and A350 are approximately six years. Even with expected production ramp-ups between 2025 and 2030, lead times will continue to increase as backlogs grow above production rates.”

With a production-demand gap of some 300 widebody aircraft today, and somewhere between 1,300–5,000 over the next 20 years, airlines will need to be flying older aircraft for longer. Are they ready for that — and is the rest of the industry?

The industry is 300 widebodies short of demand today — in 2044, that will be an order of magnitude more

Within the airframer predictions, Boeing splits the aircraft market into single-aisle and widebodies, while Airbus calls these “typically single aisle” and “typically widebody”, accounting for the overlap between — say — a Wizz Air A321neo with 239 seats and United’s forthcoming new Polaris 787-8 configuration with 219 seats. Apart from that, the market forecasts end up being fairly similar all told.

But perhaps the most striking elements from both predictions was today’s production-demand gap of approximately 1,500 aircraft total — of which 300 are widebodies — mostly as a result of production slowdowns since 2019, but also simply because demand for aircraft is outstretching supply.

Looking to the future, this widebody shortage is predicted to grow.

Boeing’s numbers — based on Cirium data and its own predictions — forecast a near doubling of widebody numbers over the next 20 years, substantially more than over the last 20 years.

- in 2004, passenger widebodies made up some 20% of the global fleet of just under 17,000 aircraft: about 3,400 jets

- in 2024, passenger widebodies made up some 16% of the global fleet of just over 27,000 aircraft: roughly 4,300 aircraft

- in 2044, passenger widebodies will make up some 17% of the global fleet of nearly 50,000 aircraft: roughly 8,500 aircraft

Boeing in another slide forecasts a widebody passenger fleet of 8,320 aircraft, with the difference to the other numbers largely due to rounding. Airbus, for its part, forecasts a demand for 8,200 new widebody aircraft over the next 20 years, which over that timescale is a fairly immaterial difference.

Overall, that’s a near doubling in widebody aircraft numbers over the next twenty years. But even at their peak production, Airbus and Boeing have never produced enough aircraft to meet that demand.

Historically, production data (from Boeing and Airbus, cross-referenced with production charts) show widebody deliveries peaked in the mid-2010s at just over 350 per year. In 2024, Airbus and Boeing together manufactured about half that number.

That gives us two edges of the manufacturing envelope between today and 2044:

- assuming 350 widebodies per year: 7,000 aircraft produced, gap of 1,300

- assuming 175 widebodies per year: 3,500 aircraft produced, gap of 5,000

Unless production capacity can be boosted permanently, world fleet demand of 8,500 aircraft, a minimum of 1,300 and a maximum of 5,000 widebodies operating in 2044 will need to be the aircraft already flying today.

That’s hard to imagine in terms of aircraft numbers, but that envelope works out as somewhere between 5 and 20 airlines the size of Emirates in 2025, which operates just over 250 widebody passenger aircraft.

But it’s not just overall aircraft numbers that matter, because widebodies are not simply interchangeable: decisions are made based on capacity, aircraft type, range, cargo, cross-fleet pilot certification, and other factors. In other words, an airline that doesn’t already operate the 787 is unlikely to simply slot in one or two Dreamliners into their fleet, but will rather look to retain commonality with its existing aircraft.

Other complications, such as the likelihood of aircraft operated by Russian carriers during times of embargo being unable to transition operators for safety and parts tracking reasons, will also arise.

That suggests that the production-demand gap will be more pronounced on an airline-by-airline basis, even before considering what cabins might be installed on board.

The world widebody fleet in 2044: more older planes, which will nonetheless need newer cabins

Taken as a whole, the numbers indicate that, in 2044, many more older aircraft will still be flying compared with the proportion of older aircraft we see today. In other words, more aircraft greater than 20 years old will still be in service, and with a wider number of airlines than in 2025.

Certainly, there are aircraft older than 20 years currently flying. United and British Airways operate 777-200 aircraft dating to the mid-1990s, which are 30 years old today, with the 777-200ER still a key part of many airlines’ fleets. Many a 767 still operating dates back to those years, or even to 1990. Early 777-300ERs are into their third decade too.

But many of these older aircraft offer sub-par cabins, particularly up front: some United 777s are pre-merger United 2-4-2 forwards-backwards flatbed, whiel BA’s include some with the second-generation 2-4-2 forwards-backwards yin-yang flatbed, and Delta’s 767s are updated but still original layout Thompson Vantage 1-2-1 staggered flatbeds, which offer direct aisle access but with constrained sleeping space. These are, by and large, cabins around 20 years old.

Inherently, airlines will need to think long-term around their cabin update strategies here, because the state of the art business class seats of the mid-2000s and mid-2020s are very different, and those of the mid-2040s will be different still.

The widebody aircraft of 2044 will largely fall into three categories, with the earliest still flying in any material number likely to be late-model versions of the 777-300ER and A330ceo.

Category 1: Aircraft no longer in production but likely still flying in 2044

- 777-300ER, first delivered 2004, final production 2021

- A330ceo, first delivered 1994, final production 2020

Critical issues here will include wider cabin look and feel upgrades to avoid these looking and feeling like old airplanes to passengers. Airlines like Delta have shown that, with careful design and investment, older aircraft like the 757 can be brought up to date to look like their newer counterparts with upgrades to bins, passenger service units, lavatories, galleys and sidewalls, in addition to the simpler seat and IFE upgrades.

A key question will be how late-model 777-300ERs can be upgraded to something approaching the width and space benefits of the new wider 777X cabin, and how A330ceos might go part of the way to matching the A330neo’s Airspace cabins.

There’s real opportunity here for airframers seeking to expand their services portfolios, but also for MRO operators and suppliers with upgrade option programmes.

Category 2: Aircraft currently in production, expected to be still flying in 2044

- A350, entry into service 2015

- 787, entry into service 2011

- A330neo, entry into service 2018

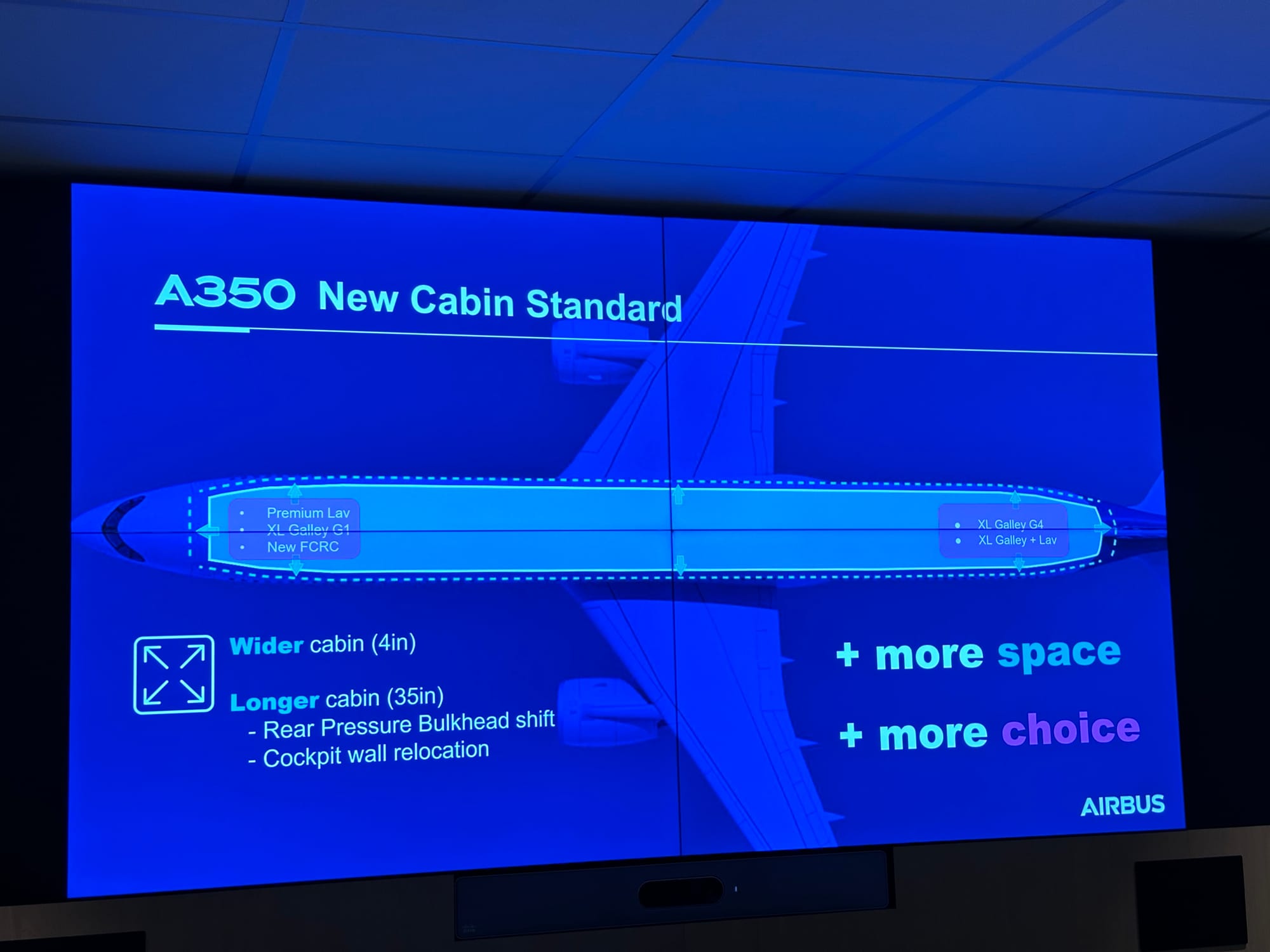

Key to managing this category of aircraft will be determining how much cabin consistency can be brought to earlier tranches of production. Already, airlines are having to manage the differences between — say — A350 New Production Standard (NPS) cabins and pre-NPS cabins. This will only increase over the decades of ongoing upgrades, performance improvements, cabin updates and other changes.

As airframers seek to roll out these cabins in linefit, it will be crucial to consider the extent to which earlier standards can usefully be consolidated. For example, what is the widebody version along the lines of A320 family bin retrofits, or

Category 3: Aircraft not yet in (full) production, expected to be still flying in 2044

- 777X

- re-engined Category 2 aircraft

- stretched or shrunk aircraft from Category 2 (and indeed the 777X in category 3)

- plus any new aircraft from Airbus, Boeing or others like Comac and JetZero

Inherently, any category 3 aircraft will need a ramp-up period to production. Boeing has a notional start with the 777X, but it has yet to enter service.

In terms of any other aircraft, took Airbus around ten years from A350 announcement to its entry into service, with the exact timeline depending on whether or not you count the pre-XWB A350 that eventually morphed into the A330neo.

Re-engining for category 2 aircraft will almost be a given during the next 30 years, and it would seem prudent for airframers to consider multiple engine options over the next 20 years, given the issues around powerplant availability, performance and reliability over the last 20 years.

Any re-engining or stretch/shrink raises the question of how — and when — to programme other upgrades as well, though, especially within the cabin. Boeing’s choice to offer the 777-style Boeing Signature Interior on the 767-400ER in 2000, which later rolled out to newer 767-300ERs, is instructive here. What similar 777X-inspired interiors might roll out to later 787s? At the same time, what’s the right balance between incremental upgrades avoiding big-bang (re)certification requirements, and larger production tranches increasing aircraft commonality?

Predicting the size and proportion of 2044’s cabins, especially up front, is a tall order

All this sets us to a number of questions for the passenger experience side of the industry: what will the cabins of 2044 look like, and what needs to be put in place in order for those cabins to be possible twenty years down the line?

Let’s start at the airframe level, then move down to the cabin and seat levels.

At the airframe level, the big question seems likely to remain the number of different classes of service, and their split in proportion of how much of the aircraft cabin each takes up. At their extremes, taking the A350-1000 as an example, today’s widebodies can vary wildly in passenger numbers:

- Qantas Project Sunrise, 238 seats

- 6 first

- 52 business

- 40 premium

- 140 economy

- French Bee, 480 seats

- 40 premium

- 440 economy

These are extremes, but somewhere in the middle, however, are most configurations, varying by more than ten percent, again on the A350-1000:

- Etihad, 371 seats

- 44 business (Zone A between doors 1 and 2 only)

- 327 economy

- Virgin Atlantic, 335 seats

- 44 business (Zone A between doors 1 and 2 only)

- 56 premium

- 235 economy

- British Airways, 331 seats

- 56 business (Zone A between doors 1 and 2 plus part of Zone B behind doors 2)

- 56 premium

- 219 economy

The most likely of scenarios is that business class and premium economy space pressure continues to push for more of the aircraft to be dedicated to those classes of service, particularly in markets where premium economy is a mature offering — which, over the next 20 years, will be most of the world.

These may well be called something different, in the way that the first class of the mid-2000s now resembles the most spacious business classes of the mid-2020s.

Increasing segmentation of economy class also seems likely: basic economy, regular economy, extra legroom economy, potentially Skycouch-style sofas, and so on.

The future scenario creates several sets of competing pressures at the front of the aircraft:

- cabin space maximisation of the section between doors 1 and 2 vs galley optimisation at doors 1 and 2 for service to adjacent and non-adjacent cabins

- desire for additional business class seating capacity behind doors 2 vs the space and certification requirements for cabin dividers behind business class

- the need to optimise for a new generation of business class seats vs the cost and complexity of moving monuments designed for cabins of previous-generation seats

Increasing flexibility at cabin level — particularly around monument optimisation — will be critical

Airframers need to make their cabins more flexible across operators, and to enable more flexibility in layout after purchase. Both Airbus and Boeing have recognised this for their current generations of aircraft: Airbus both with its New Production Standard version of the A350, and with its proposed flagship front end for the A350-1000, and Boeing with the multiple options for 777X entryways and doors 2 monuments it has been presenting in recent years at the Aircraft Interiors Expo and elsewhere.

But this needs to expand to retrofits and the aftermarket as well.

One of the issues airlines and seatmakers are currently noting about relatively early 787 aircraft now seeing cabin transition, for example, is that their ability to move monuments like galleys and lavatories is constrained, for a variety of reasons combining TSOs (Technical Standards Orders), STCs (Supplemental Type Certificates), intellectual property, and lessor requirements.

Boeing, it seems, has learned this lesson well, and is planning multiple galley positioning options for the 777X, as shown in the doors 2 area mockup renderings above and below.

Early Airbus A350 operators, too, are running into issues around expanding the relatively small galley areas at the front of the aircraft during retrofit, with competing pressures at the principal intersection points:

- front crew reset area access

- forward lavatories

- fuselage taper narrowing towards the nose

- front row of seats

- width demands of the new generation of doored suites

Ahead and behind doors 2, there are further intersection points, each one also further complicated by the competing needs of managing the interface between business class and the premium economy (or, more rarely, economy) cabins behind:

- galley space and stowage

- the doors 2 entryway pressure, including premium spaces, mini-lounges, and so on

- lavatories, including larger lavatories for disabled travellers and passengers with reduced mobility

- class-change monuments

- aisle-change space, inclduing for trolley manoeuvrability

- flight attendant seating

- on some airlines, especially those from Muslim-majority countries, prayer space

Ongoing issues with A350 lavatory production certainly do not help matters here, with focus drawn onto manufacturing rather than cabin optimisation.

Fundamentally, being able to optimise the front cabin requires flexible and space-efficient options at these principal intersection points.

As it stands, too many business class configurations have a space-inefficient filler section between bulkhead and seats, containing non-optimal elements like low-level storage, doghouses and so on.

While some modern layouts — notably those with studio class front-row suites — do provide optimisation in this area, these new products are often introduced on factory-fresh aircraft, where wider cabin flexibility, new seats, and monument space optimisation is at maximum opportunity.

Many a retrofit has suffered from the initial thinking, product design and cabin optimisation being delivered linefit, with the complexities of retrofit not considered early enough. This will have to change, for certain.

But perhaps more than anything else, the industry needs to think harder today about the needs of the future when making choices today. Decisions made on the next 787 or A350 that an airline or lessor defines will affect the entire life of that aircraft — a life that looks likely to be longer than ever before.

Continue reading at The Up Front with:

- our deep-dive analysis into the studio-class suite product generation

- Collins Aerospace’s plans to increase modularity in seats and production lines to boost the supply chain

- Boeing’s airplane, production and passenger experience challenges

- Geopolitics, A320neo successor and A350 flagship focuses at Airbus